Author’s Note: The event we will be discussing occurred one-hundred twenty years ago. Record keeping during that time period was sometimes shaky at best. We have endeavored to base our program on facts that we can verify to a reasonable degree. That being said, there are still some accounts that vary wildly. In producing this show, we have made every attempt to be as accurate as possible with records available today.

The Investigation Begins

Firefighters arrived on the scene at around three-thirty that cold afternoon with steamers set up in the Couch Place alley, Dearborn Street, and in front of the main entrance on Randolph Street. Entering the structure wearing the leather turn-out coats of the time and carrying hoses that would be carrying water at a volume and pressure considered completely inadequate today, the men managed to knock down the flames and control the fire.

Modern firefighters have high intensity flashlights that mount on their helmets, but in 1903, the fire department had only the light from open candles or kerosene hand lamps. Buildings that have burned are always very dark, even if they burned during the day. When you couple that darkness along with lingering smoke, it makes seeing anything especially difficult. Only eight days before the fire was the winter solstice, or shortest day of the year in 1903. With other buildings surrounding the Iroquois fire, limited daylight, and being inside of a large structure with only candles for light, rescuers had to grope around in the darkness for limbs in order to pull out victims.

Many of the victims were trampled or crushed to death. One report even included details of an infant found dead in a corner of the balcony, with all its clothes ripped off by people running over it.

“The jam of people coming out was so great that the firemen were unable to force their way in… I met a mob of people rushing down from the balcony. They were filling up the stairs and being trampled upon. Before this hundreds must have met death in their maddened efforts to escape”

-Chief Fire Marshal Bill Musham, Pittsburgh Press, 31 December 1903

Amazingly, a number of survivors were found underneath the dead. When rescuers discovered the living, they began piling the dead to one side and carrying out anyone who still showed any signs of life. Clothes torn away, bruised and bloodied, survivors began coming out of the building. Some who had the presence of mind were helping others and carrying children. Multiple accounts report that most of the survivors were strangely… silent.

Through the night, bodies were removed from the theatre. Totaling just over six-hundred, they were piled on wagons, horse drawn ambulances, or simply laid on top of other bodies in the street and covered by blankets and tarps.

… this is basically what happened with COVID a few years ago. And you had to think about in places like New Jersey, New York City, they had to actually convert refrigeration trucks into mobile morgues just to handle the excessive deaths. And then, there were places in South America, Spain, for example, where they had to actually convert ice skating rinks and repurpose them as temporary morgues as well. So I think as long as you do what Tim said, just treat the bodies with dignity, you’re doing right. No matter how odd or bizarre it may seem or sound, you’re just doing the best you can. -Tyler

Many of the deaths were caused directly by issues with paths of escape, doors, and lock hardware. After all of this death and destruction, good would eventually prevail. Fire code enforcement would now be strictly enforced. All theatres in Chicago were closed until they passed inspection. Other cities throughout the country followed suit and enforced existing ordinances and created new ones. Since the majority of deaths were caused by smoke inhalation (or, suffocation), and trauma caused by being trampled to death due to not being able to safely exit the building, many of these new codes focused on paths of egress, or, ways to exit.

Life Safety Lessons Learned

Today, the NFPA, or, National Fire Protection Agency, has Code 101 which acts as the “life safety bible” in use throughout this country. It clearly states that doors in the path of egress cannot be locked from the side of egress. In other words, you can’t prevent a person from walking right out of a building. Exceptions to this rule exist of course, for example prisons or other specific institutional settings, however, none of these exceptions apply to venues such as theatres, arenas, schools, or shopping malls to name a few.

As we mentioned previously, the Iroquois Theatre had accordion-style gates blocking audience members from leaving the gallery or balcony. These gates were made out of heavy iron, and probably weighed between ninety and one-hundred-twenty pounds. There were also locking mechanisms to prevent people from simply pulling the gate out of the way. These were the means of keeping a person from paying for an inexpensive seat, then moving to a better seat once the show has begun.

Now in modern times, gates like this are blatantly illegal when they block groups of people into an area. While they can be used to keep the general public out of areas such as construction zones, workers in these zones must also have clear paths of egress in order to escape a disaster. If a stadium or theatre today needs to prevent access between levels, they usually have employees at the main access to those levels who verify ticket holders seats. If the seat assignment on the ticket matches, the person is permitted to proceed. If not, they are directed to their correct seating assignment. As tedious to deal with when going to a major league game, most Americans are well used to it by now. But in 1903 the answer was to just admit people to their sections and then lock them in.

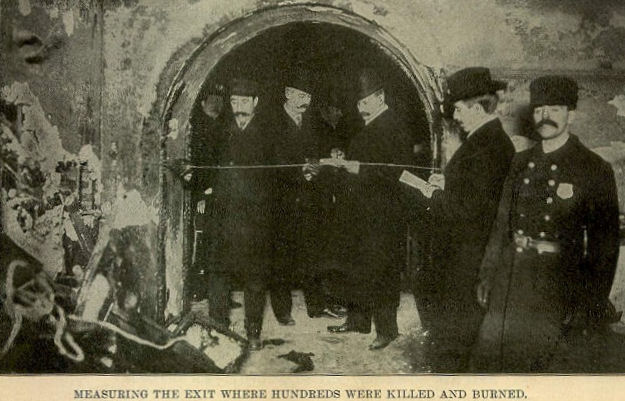

The second contributor to the loss of life at the Iroquois Theatre were the complicated bascule locks on ground level doors. While photographs and investigative reports showed that there was little damage from the fire itself on the orchestra or, parquet level, many of the deaths on this level were caused by shear human force. People piling on top of people, pushing and shoving. Stomping on other people just trying to get out resulted in deaths and serious traumatic injuries for hundreds.

Stop and think for a second about the front door of your home. Most likely it swings inward meaning, when you go to leave for work in the morning, you unlock the deadbolt and knob or lever, turn the knob or pull the lever down, and then pull the door towards you while you are standing inside. Then you step outside, turn around, and pull the door shut. Most American homes are built with in-swinging exterior doors so you are probably so used to these actions that you don’t even think about it.

If your house was on fire, things become more complicated. There is smoke and flames everywhere. You don’t know if your family or pets are with you or not, but you know you can’t turn around and go back in for them. Standing at the front door, you fumble to unlock the deadbolt and get out. Now take it even further and imagine struggling to unlock and open that door, but behind you are 20 NFL linebackers also panicked and trying to escape. Due to human nature, they run straight into you, and then into each other. And with all the combined weight against the door that has to be pulled to open, no one can actually open that door.

It’s sort of like when you have a house guest and you have to explain to them how you lift up on the door and push in, in order to get it to lock or unlock, you know, certain peculiar nuances about stuff like that. And, you know, you shouldn’t have to explain that to anyone… -Tim

Even when one of the heroes of this disaster frank houseman, a former Major League baseball player for the Chicago Colts whom we mentioned in the last episode, approached a door that had a bascule lock installed, it still took him a moment or two in order to complete the unlocking sequence. Keep in mind that the escutcheons and trim on these locks were so ornate and intricate that operation would not be immediately apparent to someone who has not used them before.

To look at modern requirements, NFPA 101 states that the releasing mechanism on a door must not require more than one releasing operation. There are of course exceptions, however none would cover the bascule locks on the Iroquois Theatre. NFPA 101 also states that a door lock must be able to be unlocked and unlatched from the egress side without the use of a key, tool, special knowledge or effort. In this case, special knowledge was obviously required as it was not as simple as pressing the bar on an exit device or pulling on a lever.

Locksmiths and door hardware installers today are required to follow not only the codes of the national fire protection association, but also all state and and local codes. Locksmiths working across multiple authorities having jurisdiction, or AHJs, should be familiar with all of their requirements. For instance, one cities’ code might simply state that hardware which easily releases the locking and latching mechanisms on a door should be installed. But in the neighboring jurisdiction, it might specify that storefront door locking and latching mechanisms have a releasing lever, or releasing paddle operator installed. And a third jurisdiction might specify that on storefront doors, a one motion releasing exit device that spans no less that two-thirds of the width of the door be installed.

I think it’s very important if you’re not sure about something, ask somebody, whether it’s the AHJ itself, co-workers, your boss, other locksmiths. I mean, you’ll get different answers from different parts of the country, which may not always apply. I’m guessing people don’t want to call up the building inspector to tattle on themselves or their customer… but there’s no shame in asking how something is done so you don’t screw it up. -Jeff

The Iroquois Theatre fire, and the lives lost within, are one of the reasons why locksmiths today must adhere to certain code requirements when installing hardware on doors. Generally, the rule of thumb is that everyone inside a building has to be able to get out, without having any special knowledge of how to operate door hardware, and without using any keys, fobs, or special tools to do so.

Aftermath

In the aftermath of the fire, Chicago mayor Carter Harrison Jr. recommended that the city council form a committee to investigate the fire. Through these actions, he ordered every theatre in the city to immediately discontinue use of arc lamps. William Davis, the manager of the Iroquois Theatre, was charged and convicted of misfeasance. These charges were later dropped however. Mayor Harrison Jr. was also criminally charged with several crimes, however they were later dropped as well.

Eddie Foy, the actor portraying sister Anne (a role that showcased his physical-comedy skills), was praised after the fire by survivors for keeping the crowd calm and remaining on stage even while burning debris fell around him. After he escaped the inferno through a coal delivery hatch, he continued performing Vaudeville acts, including one, “The Seven Little Foys” that continued until his death in 1927 at age seventy-one.

John Franklin Houseman, the former Chicago Colts player, lived until November fourth, 1922.

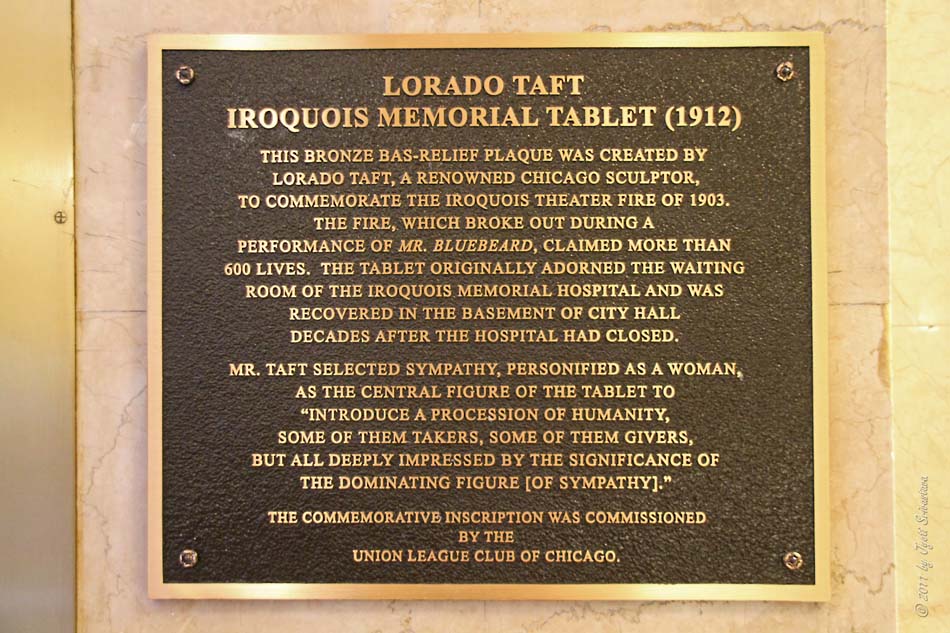

“City gets Iroquois hospital. Institution in memory of theater victims is dedicated. Speakers recall tragedy. Exercises held at exact hour of disaster seven years later”

-Chicago Tribune, December 31, 1910

The Iroquois Memorial Emergency Hospital, located at 87 Market Street, was dedicated seven years after the disaster. At the ceremonies, doctor W.A. Evans, Commissioner of Health said, “we meet here today at the time of day when, just seven years ago, those whose tragic end we commemorate were on their way to death. It is well that they should not have died in vain, but that some good should come out of their sacrifice and suffering. Such calamities should make us greater in charity, philanthropy, and blessing. They should make us realise that we are all one family.”

A bronze memorial tablet was placed in the hospitals waiting room, designed by Lorado Taft, a renowned Chicago sculptor. Mr. Taft selected sympathy, personified as a woman, as the central figure of the tablet to “introduce a procession of humanity, some of them takers, some of them givers, but all deeply impressed by the significance of the dominating figure of sympathy”.

Although the Iroquois Hospital was torn down in 1951, the plaque was saved and placed in storage for several decades. It is now mounted on a wall above Chicago city hall’s Lasalle Street entrance. The only other memorial erected for the Iroquois Theatre victims is a diamond shaped granite stone, located in Chicago’s Montrose Cemetery. Placed in 1908, it still stands in the cemetery at 5400 North Pulaski road.

As for the Iroquois Theatre itself, with the exterior walls intact, the theatre reopened nine months later as “Hyde and Behman’s Music Hall”. Later, it was renamed the Colonial Theatre. In 1925 the building was demolished. Occupying the land was now the United Masonic Temple which contained, the Oriental Theatre. Later called the Ford Centre for the Arts, it stands today as the Nederlander Theatre, having been renamed in 2019. It operates today with ‘Hamilton’ as the main production as of this recording.

During the time of the fire, a young man was in Chicago for a business trip. After returning home and learning that he narrowly escaped the tragedy of the Iroquois fire, he worked with his neighbor and boss to develop a product that would change locksmithing forever..