Author’s Note: The event we will be discussing occurred one-hundred twenty years ago. Record keeping during that time period was sometimes shaky at best. We have endeavored to base our program on facts that we can verify to a reasonable degree. That being said, there are still some accounts that vary wildly. In producing this show, we have made every attempt to be as accurate as possible with records available today.

Origins

In 1893, a nineteen year old Benjamin Henry Marshall was fascinated by the construction of buildings for the Chicago World’s Fair. Although his formal education ended in prep school, he managed to get an apprenticeship at an architectural firm from 1893 to 1895. By 1902 Marshall had established his own practice. At only twenty-nine years of age, Marshall became the architect of record for the construction of what would be known as the Iroquois Theatre.

Located inside the police patrolled “loop” of Chicago, the Iroquois Theatre was hoped to attract more women as patrons due to safety from street crimes, as opposed to areas where patrols were less common.

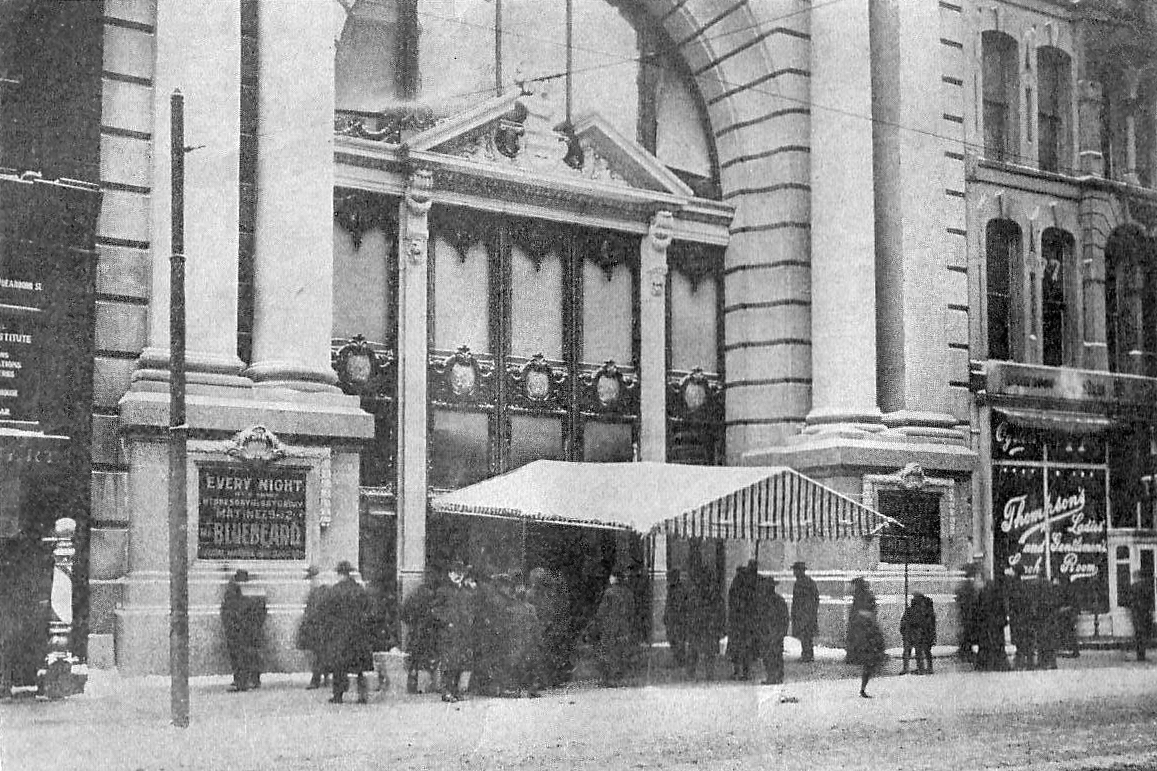

The main entrance to the theatre was located at 24 West Randolph Street, a few blocks west of North Michigan Avenue. The backstage entrance was on Dearborn Street, while the stage right scenery door was located on Couch Place. The construction of the theatre was commissioned and in part, financed by the “Theatrical Trust” or, “The Syndicate”. It was a sort of conglomerate who regulated stage productions at different venues across the country, but mainly New York and Chicago. They regulated major plays much in the same way that national cinema chains do today. Furthermore, they were known to help finance the construction of new theatres, which may have attracted the two businessmen, Will J. Davis, and Harry Powers, to collude on the project that would become the Iroquois Theatre.

And this wasn’t like… conspiracy theory or hearsay or anything like that. They had their plan leaked to a paper, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, in 1896. – Tyler

After purchasing the land where the theatre would be built, the business partners were eager to have construction completed as soon as possible. This may have been at the urging of the theatrical trust syndicate, as they were starting to face competition from several outside upstarts. Construction started in spring of 1903 with an anticipated opening in October of that same year. The theatre syndicate was facing some upstart

competition at the time and the board wanted the Iroquois construction project to be completed as quickly as possible. However, there were several labor disputes and some bad weather that pushed back the opening. Some delays though were taken care of through unscrupulous means.

I’ve heard stories over the years that back in the day here in Ohio, specifically Youngstown, that had a lot of mafia connections, that it was just common knowledge that you would show up to your building inspection with a bottle of Jack Daniels for the building inspector. I’ve also heard that envelopes would get left in certain locations throughout a building that needed to be inspected and magically they’d be gone an hour later. So… – Jeff

Design and Layout

One of the main focal points in the public foyer were a pair of grand staircases. These stairs were open to viewing by all in the main foyer encouraging a sense of “see and be seen”, regardless of your seat and by extension, the price you paid for your ticket. With fifty-three foot high ceilings, this was certainly a grand entrance bound to make even the poorest attendees feel a level of pomp and sophistication.

Throughout the foyer, halls, and audience seating, lush carpet covered the floors. Elegant draperies lined the walls and balcony fronts, and was accented with ornate wood trim throughout the building. Walter K. Hill wrote in the New York Clipper (a predecessor of Variety Magazine) that the building was “the most beautiful in Chicago” and “few theatres in America can rival its perfection”.

A somewhat unique design element of the Iroquois Theatre was that the main auditorium was situated perpendicular to the main foyer. Show-goers entered from the “stage left” side of the main theatre area, instead of from the back of the auditorium which is custom in modern theatres . This was due to an existing seven-story building located on the corner of Randolph and Dearborn streets, a building which still stands to this very day.

Theatre goers who could afford orchestra, or parquet level seating, paid premium prices. These seats would provide eye level viewing to those in attendance. They were the equivalent to modern day first class or premium seating at any event. Also, since electric sound amplification was decades away, the audience in this level could hear the actors dialogue more clearly than those in the upper sections. However, the Iroquois Theatre touted that every seat in the house was the best seat.

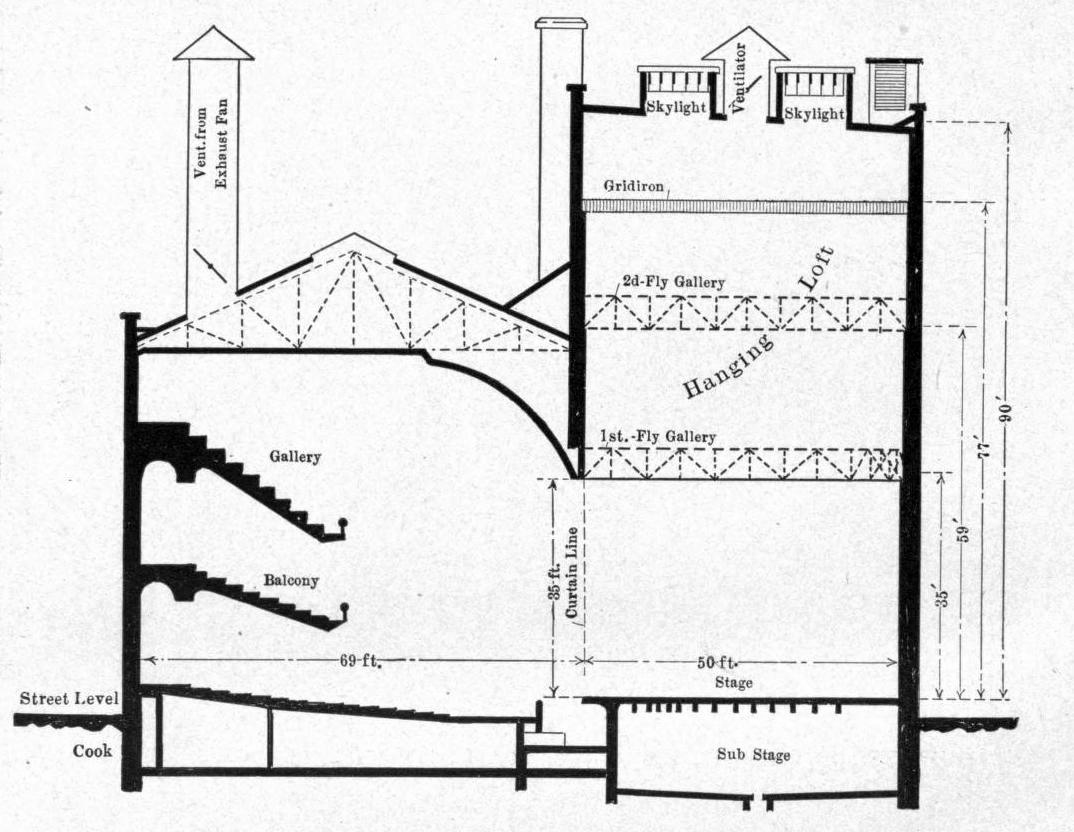

For productions such as Mr. Blue Beard, which featured acrobatics over parts of the audience, seating had been designed to give everyone a nearly perfect view of the action. The orchestra level provided seating for seven-hundred forty-four. Above the orchestra level was the balcony, or dress circle, with four-hundred sixty-five seats, and finally, the gallery, holding a total of four-hundred seventy-five seats in the top most seating area.

During construction, Benjamin Marshall was unable to produce scale drawings of the building plans to city inspectors, so accurate dimensions are difficult to come by today. When the Iroquois Theatre received its fire rating and, period equivalent to a certificate of occupancy, it was rated for one-thousand six-hundred-two people in attendance. This number, similar to ratings today, did not include theatre staff or cast and crew of the production.

Now, we’ve broken down the dimensions and actual space of the theatre to give you a better sense of the venue. From the back of the seating area to the front of the stage was sixty-nine feet, and side to side was between eighty-three and eighty-five feet. Taking additional dimensions in account, the orchestra level was approximately five-thousand eight-hundred square feet. The balcony and gallery were both approximately two-thousand eight-hundred square feet.

For comparison, an average modern day movie cinema is approximately two-thousand nine-hundred square feet with seats for about two-hundred people. This gives each person around fourteen square feet of space within the enclosure. In the Iroquois Theatre however, patrons at the orchestra level got about eight square feet per person, balcony goers had approximately six and a half square feet, and the gallery attendees had only five and a half square feet per person. None of this included ticket holders who were in the standing room only areas, places in the aisles, back, and sides of each section. Also not included in the count were the cast of between three and four-hundred actors.

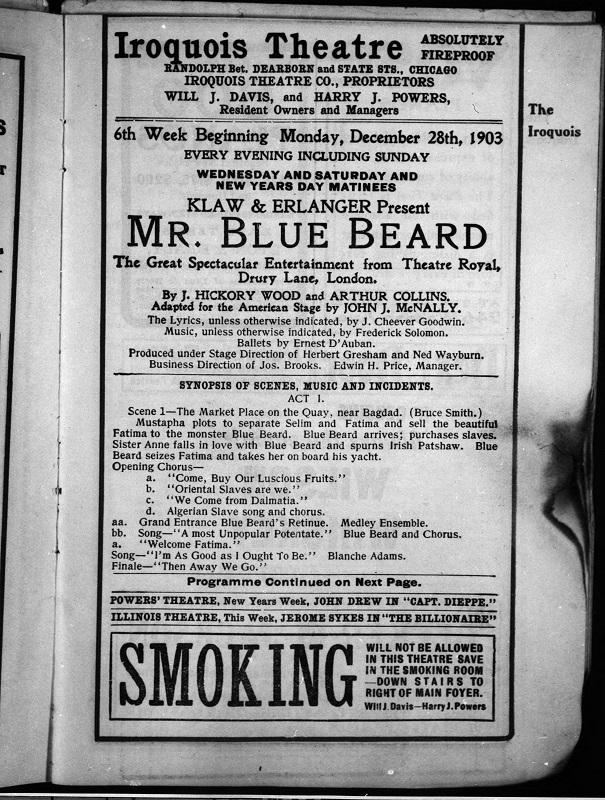

Mr. Blue Beard

The Iroquois Theatre had been running successfully since its opening, showing only one production. Mr. Blue Beard was a traditional three act play with scenes taking place in exotic locations such as Baghdad, yachts, the isle of ferns, castles, secret chambers, palaces, and even with the old woman who lived in a shoe. The play was tremendously complex in terms of scenery and the numbers of actors and stage crew to bring the story alive. Numerous painted canvases, props, and other moveable scenery lined the backstage area. The Iroquois Theatre had been designed for such large productions, having a sub-stage nearly twenty feet deep, and infrastructure going vertically nearly eighty feet to the second fly gallery. Mr. Blue Beard was marketed as a children’s play but the actual story dates back to a French tale from the 1600’s about a rich man who murders his wives and hangs them in chambers of curiosity throughout his castle.

Fire Prevention and Suppression “Capabilities”

Chicago has been, and still is known as a city of extreme weather temperatures. Being next to Lake Michigan, winters can be bitterly cold and snowy. On December 30th 1903, the day of the fire, the official recorded high temperature was fifteen degrees Fahrenheit or, negative 9.4 degrees Celsius. You might think that with over two-thousand people, plus electrical equipment and hot lights all going it would get uncomfortably warm really quickly inside. However, with the extreme cold outside, and possibly due to shortcuts during construction, the air circulation vents were closed and sealed shut. These vents were also designed as part of the fire suppression system. As we will discuss later in the series, this resulted in catastrophic consequences.

While it is hard to believe today, fires in theatres were fairly common in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s. When the Iroquois Theatre first opened in November of 1903, it was touted as being “absolutely fireproof”. Throughout the 19th century, the city of Chicago was rife with fires. The Great Chicago Fire of 1871 and several others that followed, along with frustrated insurers, put pressure on city officials to prevent future catastrophes. The solution was simple, albeit woefully inadequate. No new construction could be made out of all wood. Rather, all new buildings were required to be built with stone walls.

Now, let’s take a minute to relive eighth grade chemistry class. It takes three components to sustain fire: heat, fuel, and oxygen. This is known as the fire triangle. If you take away only one side of this triangle, fire ceases to exist. Wood is certainly a great fuel to fire, after all, who hasn’t built or been around at least one camp fire in their life? By taking away wood-sided construction in the city, it would be much more difficult for fire to spread from building to building. Officials knew that fires would inevitably happen, however the goal was to contain it to one building. Even with these building material codes though, none covered provisions for what materials could be stored inside, or how occupants of the building had to be able to exit.

Active fire suppression was common in many forms for years prior to the Iroquois Theatre fire. By 1903 there were over two-hundred-thousand building sprinkler systems installed across the United States. Sprinkler systems are actually quite simple. You have a pipe or line of pressurized water with openings spaced twelve to fifteen feet apart. These openings are blocked by plugs held in place by a piece of glass or other material that is specifically engineered to melt and give way at a certain temperature and, contrary to what movies and television would have you think, only one sprinkler head activates at a time.

Standpipes are another fire suppression system that were common in the late 1800’s and are still in use today. In a basic sense, standpipes are a direct way for fire departments to have a pressurized water supply to all areas of a building. When you go to your local supermarket, you may see a sign on the outside of the building that says “FDC” or, “fire department connection”. In the event of a fire, the fire department arrives and connects their pumper trucks to a water supply, or a hydrant, and also to the FDC. The pumper then pumps pressurized water through the standpipe system throughout the entire building, allowing firefighters to have high pressure, high volume water flow in the areas on fire. This technology had been around for several decades by 1903 and was standard practice during construction. However, the Iroquois Theatre’s standpipes were not connected to any water source, nor were they accessible to the fire department. This may have been attributed to the haste at which the building was constructed.

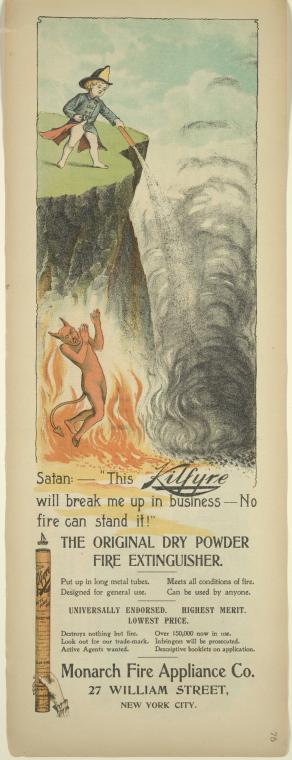

Also surprisingly common both then and now were portable fire extinguishers. Modern fire extinguishers were commonplace by 1903, having been invented almost one-hundred years prior. While not as lightweight and portable as todays extinguishers, they shared the same basic design and concept. In essence, you have a pressurized container with a chemical mixture or, just plain water, along with a valve, hose, and nozzle. In the event of a fire, you pull the safety pin, aim the nozzle at the base of the flames, squeeze the release mechanism, and sweep back and forth dispersing the chemical mixture on the fire. This would remove either the heat, oxygen, or both components of the fire, thus extinguishing it. Instead of fire extinguishers, the Iroquois Theatre had devices known as “Kilfyre”.

Kilfyre was a chemical concoction based mainly on bicarbonate of soda that, when directed onto the fire, would in theory cut off the oxygen to the fire. Operating instructions on Kilfyre devices included directions such as, “throw contents with great force at fire”, although no instructions had been provided to staff or performers. After the disaster, the devices were tested and found to be about as effective as table salt. Something that may or may not be coincidental is that Chicago Alderman John E. Scully had a side business that was involved in selling Kilfyre.

And also I want to say something about the Kilfyre sticks. The way that these were designed to be used… was basically it’s a cardboard tube that looks something similar to a road flare… and it was packed full of this fire retardant chemical in there. And the way that you got it out was you literally had to swing it like a baseball bat almost in order to expel the powder from the end of it. And that just does not seem like a good idea to me as far as simple operation, especially when you’re panicked. – Tim

Another feature that was specifically designated in the original plans was a fire curtain on the stage itself. The stage featured a grand archway, such that had not been seen in other theatres to that point. A grand curtain, made of mostly asbestos, and painted with beautiful imagery, was to hang from a weighted system in the upper area of the arch on stage. But instead of just being another decoration, it was connected to a quick release system of sorts in the event of a fire. This system had a series of triggers, both automatic and manual, coupled with counter-weights to drop the curtain in the event of a fire. Although today the health effects of asbestos are well known and documented, it was widely regarded at the time as a miracle “fire proof” material. However the curtain in the Iroquois Theatre was not a true asbestos curtain. Instead, it was made of a small concentration of asbestos, wood pulp, cotton fibers, and other material. Whether this was done as a money saving measure or simply an oversight will forever remain unknown.

Egress “Capabilities”

So the big question on all of our minds now is, how do you get out of this building in the event of an emergency?

As mentioned earlier, one of the main design attractions of the Iroquois Theatre was its opulent grand foyer. There were six entrances from the street into the lobby, and then three entrances into the foyer. The foyer entrances were mirrored as people went into the orchestra level of the main auditorium. On the couch place side of the building, there were three immediate exits, plus one exit that was connected to a stairwell. The building had twenty-seven points of exit total. None of them were marked as an exit, and some were even covered by the elegant draperies we mentioned earlier. On the balcony and gallery levels, emergency exits had also been installed, but nowhere near what we are used to today.

For people sitting in the front of the gallery, or third level, you had to turn left, climb four stairs, turn right, climb down several stairs, then turn and descend another staircase just to reach the balcony level. From there you had to descend another stairway to reach the foyer.

During the performance, accordion style gates blocked off the stairways during performances so that patrons couldn’t move down from the gallery to the dress circle or orchestra levels. This was the equivalent of movie hopping back in the early 1900s.

Bascule Locks

Since we are discussing means of egress, we need to discuss the locking mechanisms that were installed on the doors. Bascule locks originated in Europe and were very common at the time. To imagine how these locks operated, I’ll take you through a step by step description. Bascule is French for “see-saw”. In other words, they relied on counterbalance from weight to operate properly. Each door equipped with a bascule lock had a top and bottom rod that was attached to an escutcheon that acted as a counterbalance. For a modern comparison, think of the locking mechanisms on the rear doors of a semi-truck or trailer: you lift and rotate a lever to unlock the door. In the case of the Iroquois Theatre, you had to pull the door open in order to exit.

Yeah, looking at these bascule locks myself trying to make sense of them. There’s only a few pictures available of like a full door length of time period… even a locksmith, even me doing this for almost 20 years now, I kind of had to figure out how it worked. And it wasn’t until somebody kind of made that analogy to tractor trailer locks, I realized, oh, OK, that’s what’s going on here. But if you were to put me in a fire or in a panicked life safety situation, I’m not sure I could have figured it out. -Tyler

As we discussed at the beginning of this episode, we have made all attempts to be as historically accurate as possible. Therefore it is important to note that floorplans for the Iroquois Theatre available at the time of research for this episode all showed the exit doors as outward swinging. In other words, you pushed to open them after unlocking them.

Trim on any hardware these days can range anywhere from functional, to ornate. No matter the design, it never inhibits the egress of the occupants of the structure. On the Iroquois Theatre however, the bascule locks relied on the counterbalance of the trim to offset the force needed to operate the locking mechanisms. With the design and architectural style of the time, the lever mechanisms looked nothing like the modern day equivalents of bascule locks on tractor-trailers. The actual locking and un-locking mechanisms were so ornate, they appeared more like decorations than functional hardware.

The theatre was also equipped with mortise locks throughout as well. Mortise body locks sit inside a mortised out “pocket” in the door. They are either manufactured or field configured to provide a certain “function”. Modern day mortise body locks have the feature of always being unlocked from the inside, with a very small number of exceptions. In other words, if you are inside a room, you can always pull down on the lever or turn the knob and get out, no matter if a key is required to get in or not. Mortise locks had been manufactured and installed for nearly a century by this point. Unfortunately for the people who did not survive this tragedy, mortise body locks were not installed on the exit doors of this building, and as you will learn, contributed greatly to the loss of life in this disaster.

Final “Inspections”

So how was a building that by today’s standards, would be a total death trap, get passed for inspection and occupation? As mentioned at the start of this episode, certain bureaucratic dilemmas were solved by means that are definitely not appropriate by todays means. The Theatre Syndicate had large amounts of cash on hand at the time that could, theoretically, be used to influence local inspectors. Also, there were connections like Alderman Scully selling safety products to the project itself. Whether this had anything to do with the final fire inspection or not is completely unknown.

Wat is known is that Captain Patrick Jennings of the Chicago Fire Department toured the theatre days before it opened. He informed the Iroquois Theatre fire-man, William Sallers, that they had no sprinklers, no alarms, and no water connections for the standpipes. Sallers didn’t bother to report this to his chief, William Musham, for fear that he would lose his job. The general consensus outside of the project was that the building was fireproof.

So here we are building up to the day of the fire and or more so towards the opening of the theater just weeks before the fire. And you’ve got this firefighter from the Chicago Fire Department who’s doing the inspections and he’s seeing all these problems, but he reports it and he gets shut down. And you have to wonder, is that part of the sneaky stuff that’s going on… -Tim

Ninety years after the Iroquois fire, a man by the name of Rick Rescorla, after the nineteen-ninety-two bombing of the World Trade Center, was convinced that the buildings would again be a target in the future. As head of security for Morgan Stanley Bank, he spent countless hours developing evacuation plans and practice drills for employees of the bank. Perhaps if the Iroquois Rheatre had a person like Rick Eescorla, the outcome of this incident would be very different. Note: look for more of Rick Rescorla’s story in future episodes of The Three Tumblers podcast.

Back in 1903, Chicago Fire Department Captain Jennings spoke with his battalion chief, John J. Hannon about his findings with the theatre. However, Hannon told him that nothing could be done about it since the theatre already had an on site fire-man and fire-chief.

Opening

“Iroquois to open Monday, November twenty-third! Chicago’s new playhouse will be dedicated by Klaw & Erlanger’s ‘Mr. Blue Bard’ company! Theatre will seat one-thousand-seven-hundred-forty-four persons. each will have a full view proscenium-arch. Stage is one of the largest in America! Giving ample room for the spectacle!”

-The Inter-Ocean, November fifteenth, 1903.

The brand new Iroquois Theatre and the production of Mr. Blue Beard drew in massive amounts of attendees during its initial opening weeks. That was no different on December thirtieth, 1903. What was different, was that five-hundred-seventy-one humans would walk into that building to be entertained, only to perish in an inferno…